A Brief Linguistic Analysis of 한국어 (the Korean Language)

Madelyn Ferdock and Kanvi Sharma

June 2018

Abstract

Korean is a unique language because of its interaction of phonetics, phonology, morphology, and syntax. You can see this unique interaction in the way words and letters change and how they are realized depending on what case or tense mark ending is placed on them. This paper was written in conjunction with Kanvi Sharma.

The official language of the Korean Peninsula is Hangul 한글 (the Korean language) which is 573 years old. In terms of spoken and written languages, Korean would be considered a baby. It is also one of the two official languages spoken of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture and Changbai Korean Autonomous County of China. Approximately 80 million people speak it worldwide. For a long time, Korea’s official language was Chinese but in 1443 King Sejong was frustrated that his subjects were not able to express their concerns to him. From this, he created a new 24 letter alphabet that he said, “A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.”. Even the creation of the individual letters in Korean was in a very intuitive way as to allow more people to become literate (figure 1); because of this, South Korea has one of the highest literacy rates.

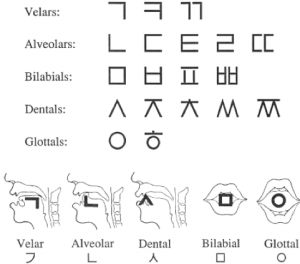

Figure 1

Here in Figure 1, you are able to see that the letters are meant to be a mirror or guide for what and where your tongue should be in your mouth. This makes reading Korean similar to reading a map of where your tongue should go and how your mouth should be shaped.

The first thing to discuss will be phonation contrasts in consonants. The Korean alphabet officially only has 24 letters; there are 14 consonants (figure 2) and 10 vowels (figure 3).

Figure 2

The realizations with an * are the tense series (also called fortis consonants) is characterized by “laryngeal tension,” whose exact phonetic characterizations are quite complex (e.g., glottal opening, the stiffening of the vocal folds, tension of the pharynx and the walls of the vocal track, high oral pressure, and the heightened subglottal pressure). These tense letters are not glottal in the sense that they are ejectives or implosives, but it is more of a clear-cut popping sound that is most similar to glottalized consonants (Yu Cho). In English, we do not have these fortis consonants or anything very similar. This makes it very difficult for native English speakers to realize this letter in the phonologically correct way. Although a native English speaker might be able to visualize the phonetically correct way for a fortis consonant to be realized, their mouth may not want to cooperate.

Figure 3

Above, in figure 3, are the vowels for the Korean alphabet. Although there are only 10 main vowels, those main vowels are combined to make 11 new different sounding vowels.

When letters are combined, they are put into syllable blocks where you stack the letters next to and then below each other in a left to right manner. For example, the word for bag, ‘gabang’(가방), uses the letters ㄱ ㅏ ㅂ ㅏ ㅇ. The spelling of this word is dictated to have two syllable blocks built around the two syllables used to pronounce. You build these syllable blocks by adding two letters together and then the next letters you add will be placed beneath these first two letters: ㄱ+ㅏ=가 /ga/ the first syllable in gabang, ㅂ+ㅏ+ㅇ=방 /baŋ/ the second syllable. This syllabic block was built by first combining ㅂ+ㅏ to get 바 and since there is still one more letter to add, ㅇ(eung), this letter is placed underneath 바 /ba/ to get 방 /baŋ/.

Certain combinations of vowels and consonants in a word create a phonological change while the morphology of the word remains the same. For example, the word eesaw(있어), the consonant ㅇ(eung) is a silent consonant unless it is placed in the bottom position of a syllable block; such as bag, gabang(가방), as seen above. In this case, the letter ㅇ(eung) is realized as, /ŋ/. However, when the ㅇ (eung) is in the top position of a syllable block and comes after a syllable block that ends in a consonant (in the case of the fortis consonant ssang shiot [ㅆ]) the consonant is realized in the second syllabic block instead of being contained to the first. It sounds like the word being said is /eetɔ/ instead of /eesɔ/.

The difference in syllabic pronunciation is also apparent when we look at the stem word of 있어 (eesaw), 있다 (eetda). The ssang shiot (ㅆ) double consonant is realized as what it is meant to sound like, a voiced alveolar fricative /ssaw/ only when followed by the letter ㅇ (eung). When the ssang shiot ㅆ is followed by a consonant or nothing at all, it is instead realized by cutting off the previous vowel very abruptly and making the following letter a fortis consonant. This unique occurrence does not only happen with the ssang shiot (ㅆ) being on the bottom of the syllable block, it happens with other regular consonants as well. This can be comparable to how in English we have letters that change the way they sound depending on where in a word they are placed and next to what letters they are.

Korean is an isolating and an agglutinating language. It forms sentences using sequences of free morphemes. Korean morphology shares a wide range of characteristics with the Japanese agglutinative morphology (primarily suffixing), invariable nouns, case indicated by postpositional particles and their use of noun classifiers. However, the sound systems and lexicons of both languages are very contrasting. Korean has been deeply influenced by Chinese in its vocabulary, encompassing a great number of words from it (Gutman and Avanzati). Certain letters also look similar to Chinese letters in their written form.

Unlike Chinese and English that have a Subject Verb Object (SVO) sentence structure, Korean sentence structure is Subject Object Verb (SOV). An example of this would be, “Saellineun (Sally) Leondeon-ae (to London) gassoyo (went).” There are no articles and definiteness is not distinguished. Although Korean limits the order of words in the way English does, its grammar imposes other types of restrictions, for instance, verb morphology is almost exclusively suffixing and agglutinative. There are around 40 different suffixes in the Korean language and these case markers or suffixes are particles placed immediately after a noun and pronoun (Gutman and Avanzati).

Case markers can be divided into four main types: honorific, tense, formal, and mood morphemes. The honorific marker ‘say-yo’(새요) is used to express respect to the subject of the verb while the formal markers ‘yo’(요) is used to convey politeness to the receiver. The suffix ‘sŭpni’(십니) is used to address somebody of a higher social status, such as the president, but also includes people who are much older than the speaker, such as a grandparent. The tense markers for past is ‘ŏsso’(었어) and for future is ‘kesso’(갰어). Tense markers for the present tense are the conjugation of a verb ‘yo’(요). Some mood morphemes that are used at the end of a verbal complex include: ‘ta’(다) (declarative), ‘la’(라) (imperative), ‘ja’(자) (propositive), and ‘kka’(까) (interrogative) (Gutman and Avanzati). Some other examples of case markers include: -neun (은), eun (는), i (이), ga (가), do (도), kkeseo (께서), e (에), man (만), and many more. An example of case markers used in a sentence is: Maikeuleun (Michael) ilbonae(to Japan) gassohyo (went). In this given example, the case marker ‘-eun’ is used after a consonant as a subject particle and the suffix ‘-ae’ is used to describe time or place, while the suffix ‘-ssohyo’ is used to signify the past tense.

These case markers are an important part of the Korean sentence structure because it helps to distinguished who is the speaker, the receiver, what type of the sentence is, and the mood of the sentence. Without these case markers, in more complex sentences, the listener would get confused what or who the speaker is actually talking about. This can be because in Korean the language does not have he, she, they. It can also be because the object particle is placed on the wrong noun making the sentence go from ‘I picked up the book’ to ‘The book picked up me’. In place of these subject words, Korean speakers use people’s names and familial terms to refer to one another. It also helps to have a native knowledge that when a speaker continues talking, it is usually about the same subject or topic at hand.

In Korean, the gender is not marked. Compared to English, the word “actor” in English refers to a male person who appears in movies while “actress” refers to a female who appears in movies. In Korean, ‘baeu’ (배우) can be used to describe both actor and actress. There is an exception when talking about family members where the prefix is placed on the familial words when referring to the mother’s side family members vs the father’s side. A good example of this can be seen in ‘chinhalmoni’(친할머니) and ‘weihalmoni’(외할머니), meaning grandmother on father’s side and grandmother on mother’s side, respectively.

Another exception when gender is marked applies to persons who are younger than the speaker and want to call upon an older person to get their attention. The speaker must then use special words to refer to an older male or older female depending on the speaker’s gender. For example, if the speaker is a female younger than the older male listener, she would refer to him as ‘oppa’(오빠), whereas a younger male would refer to the older male as ‘hyung’(형). A sentence without a first and second subject is allowed as long as the subject is implicit in the discourse. But the scratching out of the third person subject is rarer (Gutman and Avanzati). Syntactic relations between words are demonstrated mostly by postpositional markers.

Due to the heavy influence of western culture, Korean speakers have started to use some English words in a shortened form. For example, ‘remote control’ as ‘rimokon’(리모컨) and ‘combination’ as ‘kombi’(컴비) (Kim). This may seem familiar because we see this in the English language. Most English words can be traced back to foreign lands, yet we are not aware of this every time we use the word. In Korean, however, these borrowed words were adopted more recently (since the end of the Korean war in 1953) and therefore if you have a working knowledge of the English language, the speaker might be able to be more conscious of this. During the Korean war and ever since Koreans fought and still work alongside many American soldiers which is most-likely where they have borrowed these words from.

As it has been pointed out by many linguists, no language is harder than any other. To learn Korean as a native English speaker, it might be a little difficult. This is because the language and word order patterns are very different from the structure of English that the speaker already knows. The word order is also not strictly set to the SOV order in Korean. Similar to other languages, the official word order is SOV, however, there are many sentences where this order may be switched, and the listener is still able to understand what the speaker is saying. For Korean, especially, the listener has to be sure to listen to the entire sentence before responding. This is because the listener cannot glean enough information (even with a native Korean lexicon) to know what the speaker is saying before they finish their sentence.

Korean is a unique language because of its interaction of phonetics, phonology, morphology, and syntax. You can see this unique interaction in the way words and letters change and how they are realized depending on what case or tense mark ending is placed on them. The whole syntactic meaning can differ by just adding or subtracting or even placing the wrong tense or case marker at the end of the word. These are just some parts that make Korean such an interesting language to study.

Citations

Yu Cho, Y. (2016-10-26). Korean Phonetics and Phonology. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Retrieved 15 Apr. 2018, from http://linguistics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-176.

Gutman, Alejandro and Avanzati, Beatriz. Korean. 2013. 15 April 2018. .

Kim, Danny. “Korean Morphology – Anthropology.” n.d. Document. 15 April 2018. .

Good blog, who motivated you in this writing?

I really appreciate your blog post. It really covers most things about this subject. Keep it up! Don’t forget to check out my website also!

Best view i have seen for long time !